“Professor, the two maps on the PPT should be swapped.” In a history class at the Institute of Humanities (IH), ShanghaiTech, Ma Yueyang ’28 noticed that two maps on the lecture slides were mismatched with their respective historical eras. Without raising his hand or raising his voice, he pointed it out directly. Associate Professor Wang Luman heard him clearly, verified the error, and promptly corrected it. Raising hands or speaking loudly seemed unnecessary in this classroom, which, designed to hold over 20 students, had only three occupants that day—Ma and his classmate Zhu Mingxuan ’28.

This was a core course for the Foreign Languages and Foreign History major at the IH. The classroom was nearly empty, yet the attendance rate was a perfect 100%. It is not usual for a tech university to offer a humanities major for undergraduates, and it welcomed the first cohort of two students in fall 2024.

Ma and Zhu are the IH’s only two students, making them undeniably unique. Zhu quipped, “Sometimes it feels like this university only has us two students. Everyone else and their research achievements seem to belong to another university—we just happen to share the same campus.” He occasionally grapples with the question of what a humanities student “should” become. But as the “first to eat the crab,” as the Chinese saying goes, he knows the answers lie in his own hands.

Two students and 34 faculty

The IH welcomed its inaugural undergraduate cohort with just two students on September 14, 2024, marking it as “a momentous day” for IH. A group photo from that day captured 36 people: two students and 34 faculty members. Ma and Zhu, both in white T-shirts, stood at the center, surrounded by their professors.

Two students (middle in the second row) and 34 faculty.

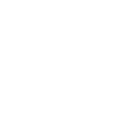

At most universities, the professor and students are separated by the distance between lectern and desks. At the IH, starting from the first class, the professor sits face-to-face with the two students at the same table for lectures and discussions, reflecting “small scale”, one of ShanghaiTech’s features, in a more tangible way.

When a curriculum designed for a full class is applied to just two students, rigid constraints fade away. The students can reject proposals, for example, to merge small classes with general education courses, or discuss how specialized seminars should be structured, or even negotiate substituting certain required courses with alternatives. As long as the cultivation framework remains unchanged, every detail is open for discussion.

Classroom engagement is direct and immediate. If not for administrative rules, Zhu imagines courses being held in a professor’s office or even the dorms. Some classes forgo screens entirely, with three desks pushed together for a roundtable discussion. A three-hour course often splits into one-hour segments each led by either the professor, Ma, or Zhu, ensuring deep participation.

A three-person class with desks arranged in a circle.

“Most course papers, if submitted early before deadlines, come back with detailed feedback,” Ma said. His paper for the course Chinese General History went through at least four drafts. Initially required to be 5,000 words, it ballooned to 15,000. “With only two students, professors can manage this. Could they manage with 20?” he asked.

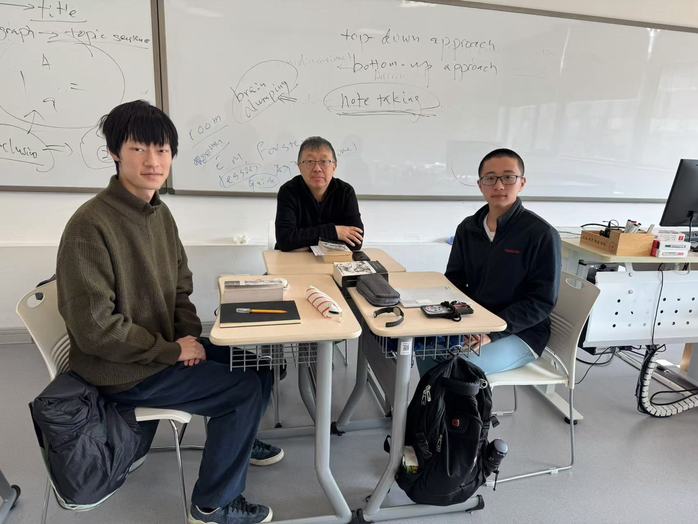

This ultra-small-scale teaching enables educational scenarios unimaginable at larger institutions. The IH is like a nascent embryo, both faculty and students are fully invested in the incubation process. As a busy professor who is also the lead for undergraduate admission, Wang Luman spends most of her time with the duo. To her, they’re “like two children.”

Zhu Mingxuan (left), Wang Luman (center), Ma Yueyang (right).

Humanities in a tech-driven university

Though the IH began admitting undergraduates in 2024, it was established in 2019 as an evolution of ShanghaiTech’s Center for General Education. While the university is renowned for its scientific achievements, general education has always been a priority. Taking the curriculum of the Computer Science and Technology major as an example, it requires students to take humanities-related courses including Introduction to Philosophy, General Introduction to Chinese Civilization, either General Introduction to World Civilization or General History of Science and Technology, plus a humanities writing course and a classics seminar.

General education at ShanghaiTech emphasizes interdisciplinary integration, aiming not just to impart knowledge but to cultivate “whole persons.”

This major, Foreign Languages and Foreign History, seeks to train students to have a background of science and humanities for global governance, being capable of understanding the historical logic of intercivilizational dialogue, leveraging cutting-edge technology for cross-cultural research, and fostering global cultural exchange. Beyond core courses, the major offers three elective tracks, including “Humanities and Artificial Intelligence.”

Designing this curriculum was no small feat. The major, rare among Chinese universities, is essentially built from scratch. Integrating language and history without disconnecting them is “a profound challenge and an art,” Wang noted. The program also aims to offer advanced integrated humanities-science options in upperclass years.

“If we can truly achieve cohesive combinations of humanities with humanities, or humanities with science, it would be a monumental achievement,” Wang said. “It’s worth exploring, and we hope these two students will help us do so.”

Why only two students in the first cohort? ShanghaiTech’s admission bar is high, even among universities in Shanghai. All majors, including humanities, require physics and chemistry as a must in the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE). Thus, admitted students are typically high-scoring students with a science background who also have a passion for humanities.

When we look back at the IH’s history, for example, its development from the initial Center for General Education to the establishment of IH, or from the inaugural Humanities Festival held university-wide, or to the first cohort of students in humanities, the liberal arts vibe has grown against the grain in a tech-driven university.

A science-to-humanities shift

The establishment of the humanities major and the enrollment of two undergraduates sparked curiosity across campus. Students from other schools dubbed them “humanities bros,” a playful nickname that made them stand out in clubs and group assignments for ideological and political education courses.

Most people’s first reaction upon hearing about them is: Why did you choose the major? Ma, with his short hair and black-framed glasses, is calm and steady. Zhu, with longer hair and an expressive personality, thrives in student activities. Despite their differences, their paths share similarities.

Ma Yueyang.

Zhu Mingxuan (first from right).

Ma, from Beijing, and Zhu, from Shanghai, both studied in elite classes in their high schools. Labeled as “smart students,” a term often tied to students good at math and science, they naturally chose physics and chemistry for the NCEE.

“Being good at math doesn’t mean you’re good at physics or chemistry,” Ma said. Math was his passion from childhood, and currently he still takes math electives at ShanghaiTech. He was not really keen on studying physics and chemistry even though he chose them for the NCEE. In his early teens, while training with a youth rugby team, he fell behind at the beginning in learning physics and chemistry and never caught up, leaving him with no interest in these subjects.

Beyond math, history captured Ma’s heart, sparked by stories told by elders when he was a child. When filling out college applications, he considered only math or history. After thorough deliberation, he turned down a direct PhD program in math at a top-tier university in Beijing due to its lack of flexibility to switch majors. ShanghaiTech offered greater freedom in switching majors and broader research opportunities in humanities. “Pursuing a PhD in Math alone would leave no room for regret,” Ma said. “I didn’t want to fix my entire life at 17.”

ShanghaiTech’s liberal teaching philosophy and small-class model were decisive for Ma. He believed the per-student resources here surpassed those at traditional humanities universities. Zhu shared this view, noting that in a class of 60 or even smaller at 20, raising every question and getting immediate interaction from professors is nearly impossible.

Like Ma, Zhu followed parents’ advice to focus on physics and chemistry in high school, even participating in research projects. But science never clicked, while philosophy held his interest. When choosing a major following NCEE, he ruled out science entirely. ShanghaiTech’s promise of a semester or year of international exchange was also a major draw.

“They both have excellent potentials in humanities,” Wang Luman said. Ma is logical and decisive, dedicating hours to study and pre-reading English materials, looking up every unfamiliar word. Zhu is detail-oriented, able to recall precise details from the first half of a 1,000-page English novel.

Quality over quantity is the mantra. Seeking promising students majoring in humanities among high-achieving science students may be a visionary approach, Wang believes. Scientific thinking will prove valuable, but passion remains the best teacher. She sees foundational significance in these two students, hoping their mutual journey will refine the program.

The first crab eaters

Aren’t they worried about being the guinea pigs of a brand-new program? Ma admits to some concern but counters, “If the first cohort isn’t trained well, wouldn’t the institute be doomed?” Zhu feels unsettled by the lack of upperclassmen to model what a humanities student should be.

Both understand that ShanghaiTech, not in the conventional China’s top university list because of its only 12-year history, lacks their prestige and public recognition. To them, undergraduate studies are for building foundations and skills, while a master’s degree is for “earning a badge.” This isn’t something to shy away from—it’s a pragmatic choice for a more valuable education.

Another question looms: Is switching from science to humanities a step backward? Does humanities have a future? In their freshman year, AI’s explosive growth coincided with many universities scaling back humanities programs, fueling another wave of skepticism about the field.

Ma is resolute. His current goal is to become a high school history teacher—not just any teacher, but an academically driven one who knows math and speaks Arabic. “I don’t want to be overly homogenized,” he said. “Homogenization leads to elimination in competition.” He believes AI will replace jobs from the bottom up, and as long as he stays above that divide, he’ll be safe.

Ma Yueyang (first from left) interning at the UN headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland.

Since the spring semester of his first year, Ma has mapped out his goals: teaching certification, English proficiency tests, driver’s license, and more, all slotted into a clear timeline. In late June, with university support, he interned for a week at the UN headquarters in Geneva, laying groundwork for his future.

Zhu, meanwhile, thrives in expressive moments, shining in theater and debate. While preparing for a debate on whether pursuing advanced degrees remains worthwhile, he embraced a perspective: advice about immediate employment or the “worthlessness” of degrees is rooted in the present. The future is uncertain, so why overthink it? Better to focus on building depth now and stay optimistic about graduation.

Zhu Mingxuan (second from right) performing on stage.

For freshmen, the future is still distant. Wang jokingly says that with just two students, faculty would “fight tooth and nail” to secure their success. Ma, with a teacherly tone, adds, “Professors can support you, but if you don’t climb upward yourself, it’s meaningless.”

Can small-scale, internationalized education deliver? What makes a humanities institute in a tech university special? What lies ahead for students who switch from science to humanities, or for the first cohort of a new major? Zhu Mingxuan sums it up: “The answer is ours to write.”