Gender equality in STEM fields is a global hot topic. ShanghaiTech’s female researchers may make up a smaller percentage of the total faculty, but they are making their mark at ShanghaiTech with their groundbreaking research and leadership.

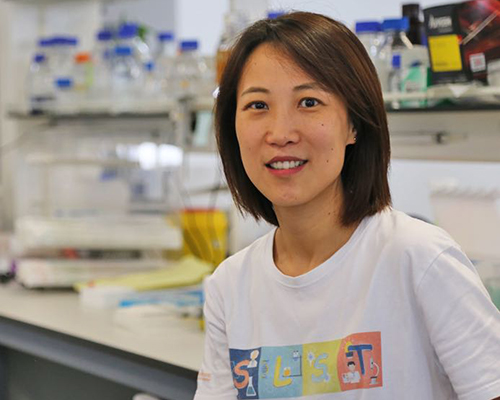

Shui WenQing

School of Life Science and Technology, iHuman Institute

iHuman Assistant Research Professor Shui Wenqing says research has prepared her well for life. “I believe doing research well trains you in almost every aspect of life: communication, logical thinking, team building, independence and language.”

After graduating from Fudan University in 2004 and doing her PhD at UC Berkeley in 2009, she did her post-doc research at Thermo-Scientific as a bio-mass spectrometry application scientist before returning to China to work as an associate professor (PI) at Nankai University in Tianjin. She joined ShanghaiTech University as an assistant professor at the School of Life Science and Technology and as a research associate professor (PI) at iHuman Institute in 2016.

Shui’s research group develops versatile mass spectrometry (MS)-based technologies for GPCR ligand discovery and cell signaling study. Her group has gained extensive experience in developing high resolution mass spectrometry-centered analytical pipelines for comprehensive or targeted protein and metabolite analysis. They’ve used their expertise in proteomics and metabolomics research to establish affinity mass spectrometry technology for ligand screening towards protein targets of therapeutic importance. They’re finding that their new approaches have some unique advantages in building a high-throughput screening platform for early-phase drug discovery as well as probing receptor-drug interactions and signaling selectivity within the cell.

According to Assistant Professor Shui, in China, kids are more exposed to sciences from a very early age, but there is less opportunity for hands-on experience. Science is encouraged, she says. Girls tend to outperform boys from early on, especially in language courses though their potential in science may not be full explored.

ShanghaiTech’s School of Life Science and Technology has a higher number of female students and also the highest number of female faculty, following a global trend. “Currently, biology is very interdisciplinary, and doing a project in biology can prepare you for a future career in lots of directions. Maybe that’s why there are more women going into life science. I haven’t experienced any strong bias or prejudice in my career path,” she says. But crucially she says, “My parents gave me full freedom to make big decisions for myself. Family support is crucial. If your family gives you a lot of pressure that may influence your decision.”

Lu Jie

School of Information Science and Technology

Assistant Professor Lu Jie arrived at ShanghaiTech’s School for Information Science and Technology 2015 after studying EE at Shanghai Jiaotong University and then doing her PhD in ECE at University of Oklahoma and her postdoc research at KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden.

“When I was younger, before high school, I was better at languages,” she admits, “but in high school, I switched my interests and I got better at math and science.” She is used to being one of the only women in the room, she says. “My female classmates went into finance or life sciences. They felt they were not good at computers. Very few women stayed in my major.”

Professor Lu’s research centers around developing new computational models, mathematical tools, and efficient algorithms for optimization and control problems to enable intelligent decision making in large-scale networked systems. Lately she’s been working on distributed optimization algorithms and autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance of UAVs (known as drones) in completely unknown environments. The drone research, which she is collaborating on with Professor Liu Xiaopei, “is designing schemes for camera-equipped UAVs to independently or cooperatively find nearly shortest paths to their destinations in an unfamiliar environment. It’s critical in aerial photography and surveillance,” she explains.

Lu has always like to challenge perceptions. “When I was younger, people told me girls were doing better in school just because they mature faster than boys, but that just made I want to work harder to prove them wrong.” Now that she is working on the drone project, she says, “I want to prove to people I can not only do the math, I can also do the engineering.”

Lu emphasizes that it’s important for researchers to follow their interests. “Everyone should choose their path. I chose academia because it allows me to choose what to do next most of the time. I want to focus on doing interesting research and publishing good papers.”

While females make up a small percentage of SIST’s faculty, Associate Dean Yu Jingyi says that the school is prioritizing efforts to attract more female faculty and SIST is doing much better than other schools of information science around China. The data shows that the number of female students at SIST have increased year on year since the school’s founding. Lu is co-organizer of Shanghai’s brand-new IEEE Women in Engineering Affinity Group, which was approved just last year. The group, she says, “unites female faculty, researchers and engineers in Shanghai so that we can regularly share common interests and concerns.” Currently she has two female students and six male students, but SIST in general has a higher percentage of female students than other schools of information science in China. “I think there’s definitely a need for more girls, not just in finance and arts,” Lu says. ”I hope there can be more. I’d like to give more opportunities to girls, but they have to be motivated.”

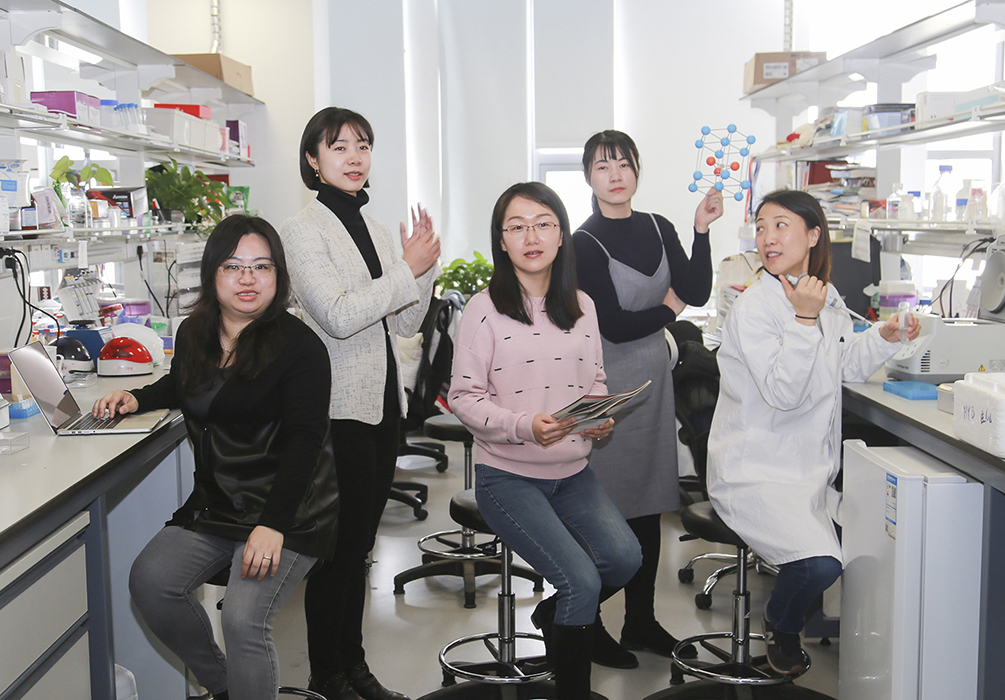

Zhuang Min

School of Life Science and Technology

Zhuang Min’s mom wanted her to be a doctor, but she had other plans. “I love to solve problems. The moment of solving a problem- I like that feeling of finding the solution,” she says.

After studying at Nanjing University for undergraduate, and traveling abroad to Tennessee for graduate and PhD studies at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital and The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, she did a post-doc at UC San Francisco and then returned to China to join ShanghaiTech in 2014 as a tenure track assistant professor in the School of Life Science and Technology.

In an article about her in Nature Methods, Vivien Marx described Zhuang’s research as melding “biochemistry, proteomics and, of late, cell biology to follow the pastimes of membrane proteins and the proteins they interact with, such as in signaling events or when a ligand docks to a membrane protein.” Zhuang told Marx that her research is akin to finding out who knows who. Her research “pioneered the development of NEDDylator, a first-generation proximity tagger based on the ubiquitin system, to find partners of proteins and small molecules.”

Zhuang says that women are relatively well-represented in life sciences in general and at ShanghaiTech’s School of Life Science and Technology. Chinese society in general benefits, she says, because there’s an emphasis on science from a young age. “Girls are just as good with experiments and your achievement encourages you to go to that area.”

Zhuang believes leading by example is important for the next generation of female researchers. She and her colleagues share support and advice to each other in a WeChat group for female researchers. “I think it is very important for students to see their advisors having a well-balanced life,” she says.

Liu Wei

School of Physical Science and Technology

Liu Wei joined ShanghaiTech in 2017, after studying at Beijing Normal University, Tsinghua, University of Tokyo and Stanford. Her research interests cover the area of solid state ionics and nanotechnology, with a focus on studies of lithium batteries, aiming at increasing the energy density and safety of the batteries. “Her studies cover battery storage for electric vehicles, phones and smart grid. “Our phone battery is not enough for our usage. We need to improve the safety,” she says. While most female researchers tend to go into life sciences, Liu was attracted to material science instead. “I like this type of study. I like to build batteries and devices, it’s really interesting. I like to use science to solve problems,” she says. She’s published 23 papers in top science journals and is a peer reviewer at ten of them.

There are relatively few women faculty in the School of Physical Science and Technology, she says, with only six females out of 60 faculty members. "The more we study, we realize there are less and less women around us. They disappear, maybe they go into industry. By the time we’re doing post-doc research, many women have married and had kids.” The phenomenon of women leaving academia for other work or to raise a family is widespread around the world, but in China, family and societal pressure have a role to play. Liu and her female colleagues often share lunch together and provide support for each other.

The issue of gender balance in the sciences is of global importance, she says. Recently, Liu participated in the Global Women’s Breakfast, an international initiative which allows female chemists to network and share information. The attendees discussed the responsibility of women in science and technology, training opportunities and work-life balance.

Dai Jin

School of Entrepreneurship and Management

Jean Dai’s decision to study women entrepreneurs was influenced directly by her experience growing up with a mother who was an entrepreneur. “I found she had a lot of difficulties,” she remembers. “Women entrepreneurship is a hot topic-you have to gain resources and fight your way to build your company.” At first, she was discouraged from pursuing gender-related research. “Experienced scholars all told me it was not that popular in management research. But after several years, gender-related studies keep showing up in top journals of management and now there are more male scholars in the field as well,” she says. “In China the ratio [of women starting their own business] is relatively high,” she says, “but the work environment is not kind to women entrepreneurs.” Jean Dai’s management research directly relates to gender parity in the workplace. Her research on the effect of ethical leadership in a business environment with male and female leaders has led to some interesting results. At the pharmaceutical company she conducted research at, she found that male leaders’ morality advance team sales performance, but women leaders don’t have that moral premium. Now she’s interpreting the results and trying to understand why that’s the case, whether it is because of role expectations, leadership styles, or some other factor. At ShanghaiTech, Dai says, the environment is good for female researchers. “I feel there are equal opportunities for women researchers and no discrimination of women here. Women in China are realizing we can do what we want.” Dai also cites ShanghaiTech's 1-2-year tenure clock extension given to female PIs in case they give birth during this time. “That’s a good signal,” she says.

Zhou Yu

School of Information Science and Technology

Back when Zhou Yu was an undergraduate student at Nanjing University of Science and Technology in 1989 there were few women in her field. “There were 10 student dorms and only one was for women,” she says to illustrate her point. But she never felt held back from studying computer science. “I just thought it was interesting,” she says plainly. After finishing her masters, she taught information technology and science for 15 years at Nanjing Forestry University. Teaching and guiding students was something she knew she wanted to do from a young age. “I was the leader even from the age of four or five,” she remembers.

Her career as Associate Dean at ShanghaiTech’s School of Information Science and Technology has helped her discover a new ability: solving problems, guiding students and faculty and creating a strong and welcoming culture for the whole community. “My work here gives me excitement, enjoyment and a whole new understanding of myself,” she says. “It’s tiring but very exciting. There something new to learn every day. ShanghaiTech is a new university and there are so many new ideas, so this was a challenge. But I like challenges. I like to learn. I think this is important.”

Zhou says her highest praise came from a foreign PI who said to her, “You can solve any problem I bring you.” From managing human resources to providing academic and student support and training, Zhou describes her job as “You can’t see me, but I’m always here helping you to solve problems.”

Zhou has a special talent for making everyone around her feel important and their opinions valued. Every week she keeps office hours so students can seek her out for guidance. “Everyone is my teacher, including my students,” she says. Every year she hosts a salon for female faculty and students to exchange. “I studied this major so I know what they’re going through. I want to give them a chance to share their ideas and issues. We’re equals, we can share our experiences,” she says.